The Combined Joint Task Forces (CJTF) concept is a NATO concept proposed in 1994 and approved in 1996 by Allied Force Commands for the command of NATO units in crisis management and conflict prevention. Today - three decades later - it is still used in numerous operations around the globe.

Meaning of the term CJTF

To better understand the term, it must be broken down into its component parts: The term force refers to a military formation or unit. A task force is an organisation with a specific, common mission. As a rule, it disbands once the mission has been completed or an agreed deadline has expired. A joint task force consists of formations / units from at least two different branches of the armed forces (army, air force, navy, space or cyber forces). A Combined Joint Task Force is made up of forces from two or more nations.

Such a CJTF is normally put together in an optimised way for a specific task. These are deployable forces, as a CJTF is not concerned with national and alliance defence, but with crisis management. As such crisis missions can be of the most diverse nature (peacekeeping, disaster relief, anti-piracy, counter-terrorism, etc.), the composition of the forces, command staff and command organisation is also different each time. The role of the command headquarters is therefore crucial in order to assemble and deploy the forces in a task-optimised manner. Like the command structure, the command system architecture in each CJTF is refined according to the mission and therefore differs from the others. It is precisely this flexibility that makes the concept so successful and durable.

Creation of a CJTF

Once the NATO Allied Council, the highest permanent body of NATO member nations, has unanimously decided on the execution of an operation, the nations are requested to provide force generation - the provision of forces including command and staff personnel. Normally, one nation will provide the Operations Headquarters (operational planning level) and another the Force Headquarters (tactical execution level). The staffs of these headquarters will be multinational.

Network Centric as a prerequisite

A unit made up of different nations and branches of the armed forces faces one major challenge: interoperability. This refers not only to technical interoperability, but also to procedural interoperability and working together as a single unit. The CJTF concept coincidentally coincided with the technological step towards open architectures, which in theory would allow the implementation of network-centric warfare.

The NATO Operation Allied Force in 1999, for example, showed how little interoperability there was between its members. While the British, Germans, Italians and Dutch still operated reasonably effectively together, it seemed as if the Americans and French were operating outside of NATO procedures.

This improved with the NATO operations after 1999 in Kosovo (KFOR) and from 2003 within the NATO-led ISAF alliance in Afghanistan. As these operations lasted for many years or are still ongoing today, interoperability was able to develop significantly in technical and procedural terms and the nations were able to prepare their respective units accordingly prior to deployment. Military formations from non-NATO members were also integrated here for the first time.

Plug-and-fight as a goal

In the context of network-centric warfare, the US armed forces demanded and achieved for themselves the ability to plug and fight in the sense of seamless integration into an operation, but this was never really achieved on a multinational level. On the one hand, this is due to the different pace of technological development within the alliance and the partner countries; on the other hand, the technical architectures (e.g. the command and control information systems) are different in each operation, depending on which nation is in command. This places high demands on the equipment, training and flexibility of the deployed multinational forces.

Horn of Africa revealed the challenge

Around 2010, four Western maritime task forces were operating in the Horn of Africa: Task Force 150 in the US-led Coalition-of-the-Willing ENDURING FREEDOM against international terrorism, Task Force 151 in a UN operation against piracy, the EU Naval Force ATALANTA to protect the ships of the World Food Programme against Somali pirates and a NATO task force in Operation OCEAN SHIELD against terrorists and pirates.

Although these task groups also co-operated with each other, they always did so within certain limits in terms of their mission and technical and tactical capabilities. Switching back and forth between operations would have been desirable according to the Net Centric Warfare concept, at least for the units of the NATO nations, but in reality would only have been possible with several days or weeks of preparation due to the different command systems and structures used. No thought of plug-and-fight. The CJTF concept itself does not offer standardised, cross-operational integration for the tactical level. Even more important, however, are the legal hurdles for such short-term reorganisation: in most countries, participation in a specific operation requires a corresponding political mandate.

New players in the operating theatre

But completely different, new players revealed the need for better and much broader interoperability at the time. The situation picture concerning merchant ships in the Horn of Africa was created and distributed by the UN's own civilian International Maritime Organisation (IMO) and the EU's own military Maritime Security Centre - Horn of Africa (MSCHOA). Through both organisations, relationships were also established with Asian, African and US organisations of maritime interest groups and industries, whose information and cooperation was and still is crucial for curbing piracy in the region. During the peak phase of ATALANTA, the German Armed Forces developed close interdepartmental working relationships with the Federal Police and the German judiciary.

Afghanistan and the Balkans had already shown how important it is to have knowledge of the civilian forces of other ministries and non-governmental organisations in the area of operations and to cooperate with them.

NATO focusses on multi-domain operations

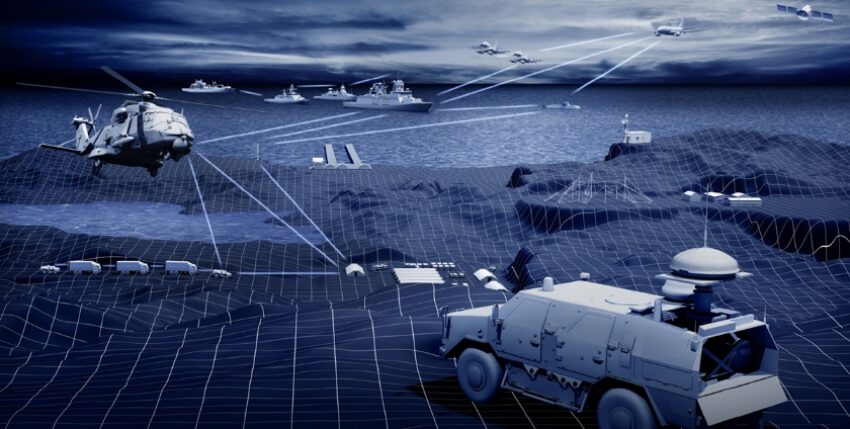

NATO's Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) concept is aimed at such cooperation. It was approved in 2023. NATO distinguishes between a total of five operational dimensions (domains): Land, air, sea, space and cyber. In contrast to the term joint, the focus here is not on the armed forces deployed, but on the dimensions in which an effect or effects are to be achieved.

The Bundeswehr translates the NATO definition of MDO as follows: "Orchestration of military activities across all dimensions and environments, synchronised with non-military activities, to enable the Alliance to create overlapping effects at the required speed."

The cooperation between branches of the armed forces - i.e. the joint concept - remains at the core of MDO. The main difference between joint and multi-domain operations lies in the depth and quality of integration in terms of the "required speeds". NATO also refers to this as an "evolution of joint operations". The second focus of MDO is on synchronising military operations with non-military activities in the theatre of operations.

A prerequisite and defining feature of MDO is the comprehensive and seamless connection of all elements involved at tactical and operational level. The purpose is to shorten the time between detecting the target by sensors, deciding on the required effect and triggering the effector. This so-called "sensor-decider-shooter-chain" requires seamless integration through the broadest possible networking without vulnerable nodes. It is of secondary importance from which platform or in which branch of the armed forces these three processes are provided. The quality and speed of data processing are the key to success.

Synchronisation with non-military organisations

This applies not only to the use of weapons but also, in a figurative sense, to the achievement of non-kinetic effects, be it through other civilian players in the theatre of operations. The long-term evolutionary goal of MDO is the transformation of networked operations management into a data-centric type of operation that also includes these non-military organisations. The MDO concept states that non-state stakeholders are not subject to the military chain of command, but that non-military actions must be synchronised with military activities. This means that military and non-military actions should be embedded in a whole-of-government approach wherever possible. Military operations become more effective when they are flanked and supported by non-military actions - and in most cases this realisation also applies vice versa. Military and civilian command and control systems therefore require interfaces through which information can be exchanged without delay. The operational principles and principles of the military and civilian organisations must also be known to each other.

Conclusion

The CJTF concept is neither a NATO invention nor a NATO unique selling point. The USA has been operating according to a national CJTF concept since the early 1990s, which NATO adapted in 1994. One of the USA's aims was to involve allies and partners more closely and to increase their involvement in the conduct of joint operations. In the meantime, other supranational organisations such as the United Nations or the European Union are also conducting operations based on the concept. At the military-operational level, the CJTF concept is highly successful and still up to date. At the tactical level, however, the quality of integration and the speed of weapon deployment processes are now lagging far behind the technological requirements.

For the German Navy, cross-sectional sensor-shooter integration is still being prevented by the variety of systems driven by industrial policy and the simultaneous lack of standard interfaces. A lack of cooperation and a lack of dynamism among those responsible for the process is preventing the automation of situation picture generation and combat planning that has been demanded for many years - a basic prerequisite for the MDO capabilities at tactical level described above.

Even though the MDO concept focuses on national and alliance defence, it offers important points of reference for CJTFs geared towards crisis operations. The MDO concept offers answers to deeper integration of forces as well as the decision-making and implementation level with the aim of providing effects (both lethal and non-lethal) in the required time. MDO makes the integration of other stakeholders in the operations room a system-critical requirement. MDO further develops Network Centric Warfare into Data Centric Warfare.

Achieving such a pronounced MDO capability is a long way off. Questions about flatter C2 structures, deeper system integration, more comprehensive architectures and synchronisation with non-military partners need to be answered. The CJTF concept has a great chance of being accompanied by this development in the future.

Frigate Captain Andreas Uhl is co-author of the Multi-Domain Operations Concept published by NATO Allied Command Transformation in April 2023. He is currently serving in the Naval Command.

Andreas Uhl