Despite the military inferiority of the young US Navy, it was ultimately victorious against the Royal Navy. It received important support from France.

A resolution passed by the US Congress in October 1775 not only stipulated the dispatch of a militarily equipped sailing ship (see box), but also authorised a second one for the same purpose. It was also decided to form a committee of three, later expanded to 13 members, to oversee the acquisition, equipping and deployment of the warships. The drafting of this short document is officially recognised as Birth of the US Navy.

This was preceded by a decade or so of constantly rising tensions between London and the North American colonies, with the exception of Canada. The Continental Congress was established in 1774 to coordinate and represent the interests of the thirteen colonies between Massachusetts and Georgia. After the first spontaneous skirmishes between colonial militias and the British army in the spring of 1775, the Congress inevitably developed into the de facto government of the American independence movement.

On land, the Americans proved themselves in battle musket against musket. In March 1776, the British army was even forced to evacuate Boston and other large areas of New England. However, the Royal Navy dominated the seas. The British command of the sea routes did not stand in the way of sending reinforcements and supplies. The British fleet was also able to blockade the most important harbours in the secessionist territories in order to prevent the supply of weapons and munitions from abroad. General trade was also to be cut off in order to bring the colonies to their knees. The economic damage mainly affected the export of agricultural products and raw materials to Europe as well as trade with the colonies of various nations in the Caribbean.

In 1775, the Royal Navy had a total of 270 operational units, only a fraction of which operated in the American sea area, but which were generally better equipped and manned than their opponents. The American colonies had numerous smaller merchant ships and shipyards, but no armed units. From 1775, some colonial militias provisionally equipped smaller merchant ships with cannons on their own initiative. George Washington, commander of the united land forces of the colonies since June 1775, also had a flotilla of twelve ships raised under his command. However, these units were not led by experienced naval officers, but by army officers and soldiers. Their deployment was largely limited to disrupting British supplies in the immediate vicinity of the coast.

First flotilla

Congress recognised the need for a centrally commanded navy that would be able to counter the British forces at sea. Two weeks after the first authorisation on 13 October 1775, the procurement of two more ships was ordered. The four former merchant ships were refitted in the harbour of Philadelphia. The rigging was realigned and the hull reinforced and fitted with gun hatches. At the end of December 1775, they were assembled into the first flotilla of the American navy and brought together at the mouth of the Delaware River. The merchant ship BLACK PRINCE, which had previously travelled the transatlantic route, was designated the flagship under its new name ALFRED as the largest unit with 30 guns. She was followed by the COLUMBUS with 28 guns and the brig ANDREW DORIA and CABOT, each of which had 14 guns. Two sloops and two schooners were added over the next few weeks.

of the US Navy, graphic: US Navy

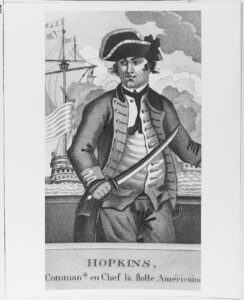

There was no shortage of experienced sailors and shipmasters. Only a few of the officers had previously served in the Royal Navy, but many had already had a considerable career as privateers or merchant ship captains. Some of them had already gained experience during the Seven Years' War between 1756 and 1763. These included Esek Hopkins from Rhode Island. Over the course of almost four decades, the 57-year-old had travelled the North and South Atlantic waters and the Caribbean as a merchant sailor and got to know every important port. He learnt the trade of war as a privateer and later as a brigadier general in the Rhode Island militia. Congress appointed Hopkins commander of the American fleet known as the Continental Navy on 22 December 1775.

Debut

The Congressional Naval Committee gave Hopkins his first operational order on 5 January 1776. The small American flotilla was first to sail southwards from Delaware Bay into Chesapeake Bay to seek battle with British ships and then sail down the coast with the same objective. However, Hopkins was authorised "if adverse winds or stormy weather, or any other incident prevent it", to proceed otherwise at his discretion "in order to injure the enemy by any means at his disposal". The commodore interpreted this passage very generously and set sail for the Bahamas on 17 February 1776. His aim was to secure the British black powder stocks stored in Nassau and bring them to America. Hopkins actually succeeded in landing 200 marines and sailors on 3 March, who captured Nassau and the two neighbouring forts without any significant resistance. Although the commodore failed to achieve his main objective (the British governor was able to evacuate 80 per cent of the powder kegs on a fast sailing ship in time), the American troops secured 63 fortress guns and other ammunition.

On the return journey towards Rhode Island, the American squadron encountered three British ships. On 4 April, Hopkins' convoy brought the schooner HMS HAWK It was the first American victory over a British warship.

Contrary to the usual practice, the captured warship was not taken over by the American fleet, but sold as a prize, which indicates heavy battle damage. Shortly afterwards, a transport ship with powder and ammunition was also captured. Finally, on 6 April, a running battle lasting several hours took place against the British frigate GLASGOWwhich ultimately escaped.

The captured weapons and ammunition came in handy for the poorly supplied American land forces. The first operational successes of the American fleet recorded during this voyage strengthened the American will to persevere.

Cargo ship with gun hatches

The expansion of the fleet was continued in a targeted manner. Even before the official declaration of independence on 4 July 1776, a fleet of 27 ships was declared. In terms of numbers, this was already the highest level. As the naval war intensified, losses and new additions to the Continental Navy were balanced at best. However, over time, larger and more powerful warships were introduced, increasing the fighting power of the American Navy.

The sources of supply were also expanded. The first unit built as a warship at an American shipyard from the outset, the 32-gun frigate RALEIGHwas launched in May 1776; the first operational voyage began in August 1777. A total of ten frigates were completed in American shipyards over the course of the war. They were generally smaller - and thanks to the use of lighter types of wood - faster than their European counterparts. American envoys in Europe also managed to acquire some ships abroad during the course of the war. In order to preserve the temporary neutrality of the European states, the units were formally labelled as merchant ships when purchased, especially in the early phase of the conflict. The first example is the frigate DEANEwhich was commissioned from a shipyard in Nantes in 1777. Local authorities only became suspicious when they realised that the "cargo ship" was equipped with 32 gun hatches. However, the shipyard operator was able to produce a forged purchase contract that excluded any foreign involvement. Captured British ships were added as a third pillar of the fleet build-up.

Marines on the Bahamas island of New Providence on 3 March 1776, oil painting by V. Zveg, 1973, illustration: Naval History and Heritage Command

The Royal Navy still enjoyed a numerical advantage of ten to one, with even the largest and most heavily armed American units unable to match the fighting power and resilience of the British heavy ships of the line. It was clear from the outset that the American fleet would have to rely on asymmetric warfare. Mobility, speed and unpredictability became the most important attributes of the Continental Navy.

The hunt for British merchant ships and military transport convoys was a key element of the American strategy. This secured important supplies, including weapons and ammunition for the American army and navy, and weakened the supply of British troops accordingly. The Royal Navy was forced to deploy additional units for convoy escort duties and patrols in Atlantic and Caribbean waters, which weakened its offensive potential.

Added to this was the targeted hunt for British warships and privateers. While the American warships always had an advantage over the privateers, the chances of success and risks always had to be weighed up against the warships of the Royal Navy. During the first phase of the war, the focus here was on fighting British blockade ships, especially as the British Navy favoured lighter units for this purpose during this period. Over time, however, the blockade fleets were reinforced and became largely unassailable.

From 1777 onwards, the Continental Navy increasingly shifted its operations to the high seas in order to intercept British supply convoys in the middle of the North Atlantic. Several missions to devastate British supply stations and whaling harbours in Nova Scotia were also carried out in order to disrupt British supplies for troops in North America. In July 1779, Commodore Abraham Whipple succeeded in a particularly daring endeavour. In a fog bank off Labrador, his squadron of three ships encountered a supply convoy under the escort of the Royal Navy. Hoisting the British flag, Whipple's ships mingled with the transport ships and brought up a total of eleven units without being noticed by the British warships.

In the lion's den

The most dramatic were the advances by American captains into British waters. The first such venture took place as early as October 1776 with the dispatch of the 18-gun brig Reprisal under Captain Lambert Wickes to France. The Reprisal reached Nantes at the end of November, where the designated American envoy to the French court, Benjamin Franklin, disembarked. Between January and June 1777, Wickes undertook two voyages of war from French harbours, first along the Bay of Biscay and the English Channel and then in the Irish Sea. On these voyages, he mustered a total of 19 ships, including a courier ship armed with 16 guns. Wicke's decision to bring his prizes into French harbours, which were still neutral at the time, led to fierce protests from the British government. For this reason, the Reprisal temporarily detained by French authorities.

Wickes was followed by Gustavus Conyngham, who travelled the North Sea, the Mediterranean and the waters around the Azores between July 1777 and September 1778, operating from neutral Spanish ports. During this time, Conyngham mustered 60 British ships, of which he sank 33 and took 27 as prizes. The economic war had an effect. British shipowners' insurance costs rose to 28 per cent of cargo value, higher than at any time during the Seven Years' War. British merchant guilds began to propagate an end to hostilities.

Finally, Captain John Paul Jones' voyage to Europe provided another highlight. On 22 April 1778, sailors and marines from his slup Ranger The British invaded the British harbour of Whitehaven with the intention of setting fire to the 200 merchant ships anchored there. The operation ultimately failed when his crew failed to capture one of the harbour forts. Nevertheless, the attack caused panic along the entire English coast. The population and town councils demanded troops to protect them from future raids. In fact, the Royal Navy was forced to increase patrols of home waters. This was inevitably at the expense of offensive capability - the Continental Navy's calculation had worked out.

Equal opponents

Jones remained in European waters and continued to threaten British shipping from Brest. He achieved two much-vaunted victories against British warships. In April 1778, after an hour-long heavy battle, he forced the British sloop Draketo lower the flag. It was the first victory of an American unit against an equal British warship - and this directly off a British harbour.

John Barry travelling frigate Alliance,

made by a person serving on board

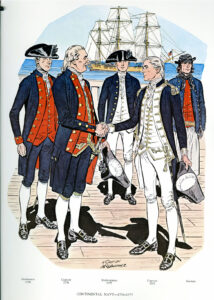

Officer of the Naval Infantry, illustration: Naval History and Heritage Command

In February 1779, France handed over a frigate armed with 44 guns on loan to the USA. Jones took command and gave the ship the new name Bonhomme Richard. Between August and October of the same year, Jones commanded a mixed squadron of French and American ships in British waters.

On 23 September 1779, the most dramatic naval battle of the war from an American perspective took place. Off the coast of Yorkshire, the scout of the Bonhomme Richard a British convoy consisting of 40 transport ships. Jones rightly surmised that the ships were importing timber, canvas, sailcloth and other products necessary for shipbuilding from the Baltic. The convoy was led by the 44-gun frigate Serapis and by the converted merchant ship HMS Countess of Scarborough. The two warships changed course to intercept the four approaching enemies.

Navy from the period 1776 to 1777, illustration: Naval History and Heritage Command

The Serapis and the Bonhomme Richard opened fire almost simultaneously at 6 p.m. from a distance of 90 metres and continued to close in on each other. In the course of the battle, however, the ships became so entangled that their respective escorts were unable to intervene. Most of the battle now took place at close range with the use of cannons, muskets and hand grenades. Repeated boarding attempts by both crews were bloodily repulsed, but both ships took on water. Finally - after almost four hours - an American sailor managed to fire hand grenades from a yard into a deck hatch of the Serapis to throw. They landed under powder kegs on the gun deck. The devastating explosion brought the decision. The British captain Richard Pearson struck the flag. Ironically, it was the Bonhomme Richard which sank, so that Jones had to fly his flag on the Serapis changed. After making makeshift repairs, Jones led his two prizes - the French warship Pallas had in the meantime Countess of Scarborough defeated - in the neutral Dutch harbour on the island of Texel.

With a Little Help

This last great voyage by Jones highlights an important factor. The Continental Navy's naval feats had a great impact on both a tactical and psychological level, but would not have been enough to break British naval supremacy on their own. For the young American navy, the war was always a David versus Goliath struggle with correspondingly high American losses. In the course of the entire conflict between 1775 and 1783, only 57 ships flew the flag of the Continental Navy at any one time. Of these, 21 were classed as frigates. Some of the frigates built in American shipyards were not used at all because British blockading squadrons prevented them from sailing.

The treaty of friendship signed by Paris with the United States of America in February 1778 was accompanied by a military assistance pact. From then on, France openly supplied the USA with war materiel and led the supply convoys. One of the most important aspects of the alliance was the deployment of the French fleet, which was equipped for conventional line warfare, against the Royal Navy. Spain also declared war on Great Britain in 1779, followed by the Netherlands in 1780. The British fleet, which had been expanded to almost 500 units by the end of the war, was surrounded and overstretched. The dispatch of a French fleet of 28 ships of the line to America in 1781 forced London to realise that the supply and deployment of British troops in America was no longer guaranteed. London agreed to peace talks.

However, America quickly forgot the importance of its navy. After the official end of the war, the fleet was completely decommissioned in order to save money and pay off the war debt. The consequence of this peace dividend: American merchant ships were helplessly exposed to the activities of North African corsairs as well as French privateers. In 1794, a new naval law was passed authorising the construction of six powerful frigates to protect American interests. The development of the US Navy into a major maritime power would take another century, but the first steps had been taken.

Sidney E. Dean