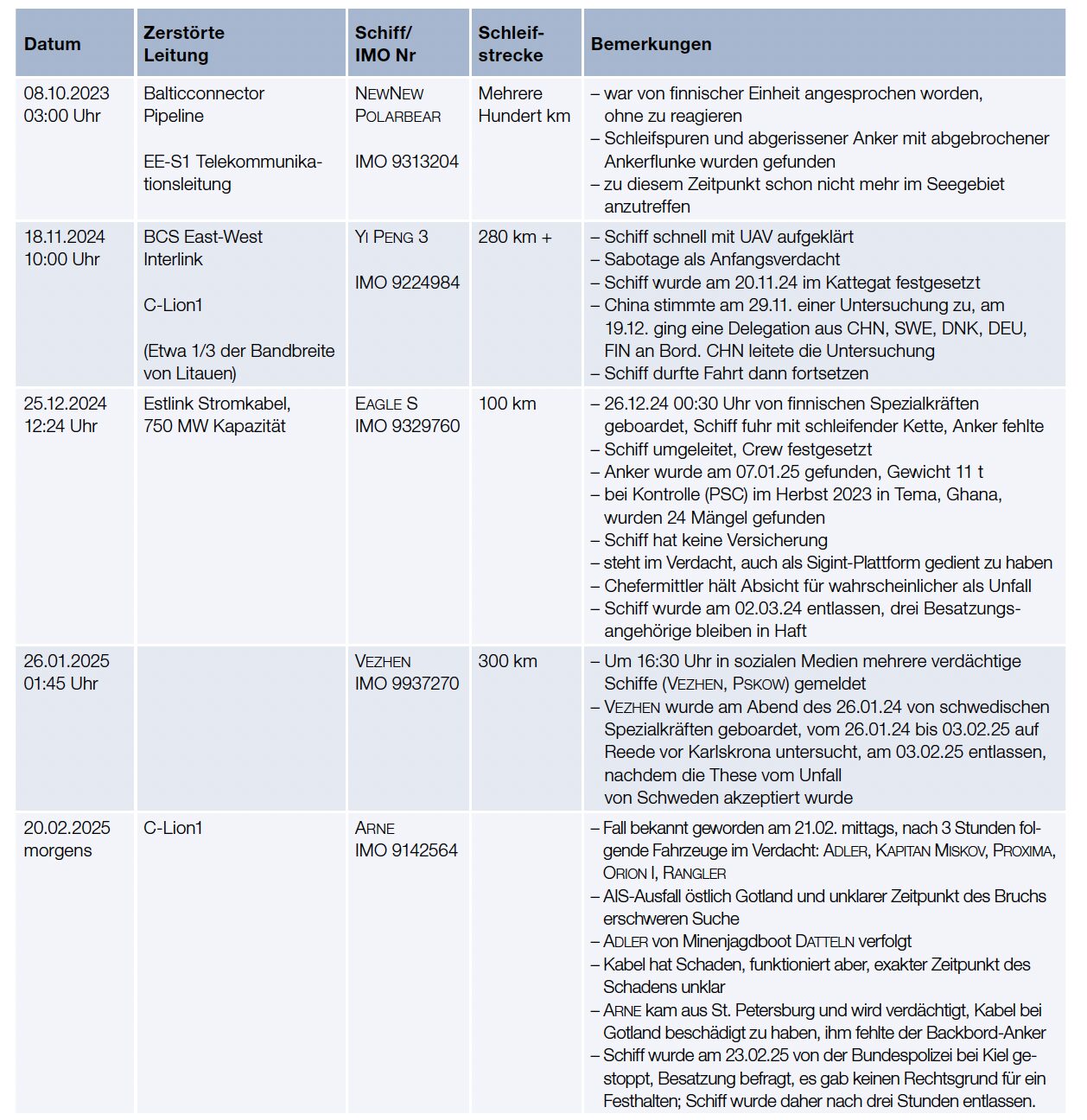

There have been at least five incidents in the Baltic Sea in the last year and a half in which cargo ships have damaged deep-sea cables or pipelines with their anchors. Were these accidents or deliberate acts?

When looking at these cases, the following similarities become apparent:

1. the ships came from Russia, were carrying cargo for Russia or the Russian shipowners or owners had close economic ties with Russia. From the EU's point of view and with particular regard to the existing sanctions regime, the shipowners were acting at least in the grey area. Some had Russian crew members on board. crew members on board.

2. the ships travelled very long distances with dragging anchors.

3. the crew claims not to have noticed the anchor slipping and that they simply continued sailing for many hundreds of miles, even if the chain or an anchor fluke broke.

4. the ships exhibited various technical defects. These had either been identified during current inspections or, in the case of the Eagle S, during earlier inspections.

5. the ships are not or only insufficiently insured.

Many readers of marineforum have sufficient nautical expertise to be able to judge whether you can release your anchor unnoticed and then sail many miles. Nevertheless, an attempt should be made to quantify this thesis. Around 200 cable breaks occur worldwide every year, of which around 50 are caused by anchors. The Baltic Sea accounts for around 0.12 per cent of the area of all the world's oceans. This means that 0.12 per cent of 50 cable breaks per year should occur in the Baltic Sea. That would be 0.06 cases per year. If we assume that the 200 cable breaks can only occur in sea areas with water depths of less than 100 metres, because an anchor generally does not reach any deeper, then we would not have to use the entire sea surface as a reference value, but only those sea areas that are shallower than 100 metres. That is about ten per cent of the sea surface. This would result in 0.6 cases per year in the Baltic Sea, which is significantly fewer than the five counted in the past 18 months.

This discrepancy is confirmed by other experts: In a social media post from 26 January 2025, various analysts attempt to statistically assess the frequency of cable breaks

In any case, the authors come to the conclusion that this is an unusual accumulation of cases. One analyst has calculated that such an accumulation of cable break accidents can only occur every 108,000 years. However, the question can also be approached differently. Despite intensive research, there are simply no documented cases of a seagoing vessel travelling several hundred kilometres with a dragging anchor. This makes it all the more unusual when this happens several times in the same sea area. The typical situation in which comparable damage occurs is also different: Anchors usually damage cables and lines when a ship accidentally anchors in a place where cables are laid, for example near harbour entrances or in harbours when there are problems with the engine. A cable can then be damaged when the ship drops anchor. The fact that five times in 18 months a ship with a dragging anchor travels more than one hundred kilometres on the high seas is an unusual occurrence.

Counter-arguments put forward in the discussion are that the ships were travelling on autopilot or that the crew was overtired, and that various technical equipment was allegedly defective on one occasion or another. In this respect, it is possible that they did not realise that they were sailing with dragging anchors. A closer look at some exemplary voyage profiles of

Schiffen illustrates the inconsistency of such explanatory approaches:

- The long dragging distance: a ship drags an anchor for ten hours over a distance of more than one hundred kilometres at a speed of six to eight knots. During this time, two to three watch changes must have taken place, during which the officer on watch would have checked the condition of the ship and noticed a dragging anchor.

- Course and speed changes: The voyage profiles of all ships observed by AIS show multiple course changes, for example when passing a traffic separation scheme, as well as an increase or decrease in speed while the ships were dragging their anchors. The Yi Peng 2 made a full circle at around 09:10 UTC on 18 November 2024 and then increased her speed back to ten knots. She presumably weighed anchor at this moment. The Eagle S made a full circle on 25 December 2024 at around 11:45 UTC after passing the EstLink 2 cable. The Vezhen also made a full circle on 26 January 2025 at around 06:30 UTC. Travelling a full circle, which was observed in three of the four cases considered, is a very rare occurrence in merchant shipping. It presupposes that someone is actively steering the ship - the autopilot does not make full circles.

Proof is missing

In any case, one thing is important: the details presented here as examples are merely indications and, at best, provide circumstantial evidence. They are not proof that the damage was caused intentionally. It is always possible that there is another explanation for what happened. For example, they could stem from the poor technical condition of the ships. Mats Ljungqvist, the Swedish chief investigator in the Vezhen case, has blamed technical failure and poor seamanship for the latest incident in this series. And yes, there are always reports about the poor condition of Russian ships. An investigation of the Eagle S also found various technical defects. During the Port State Control (PSC), a kind of technical inspection for ships, on 8 January 2025, 32 serious defects were found. Among other things, the ship had no functioning radar (!) and had already attracted attention due to various defects during an earlier PSC inspection in Ghana in 2023. As often observed with other ships in the Russian shadow fleet, the Eagle S also had no insurance. A series of incidents in recent weeks illustrates the generally poor technical condition of the ships sailing for Russia. On 11 January 2025, the fully laden tanker Eve ntin was brought to Sassnitz by emergency tugs. It had previously been drifting north of Rügen with a defective propulsion system. During the same period, the freighter Jazz attracted attention in the Baltic Sea because its engine kept breaking down. On 26 January 2025, the tanker Unity was reported to be drifting without propulsion in the Bay of Biscay. All three ships are sailing for Russia and had no challenges in keeping their anchors on deck, despite their overall technical condition being demonstrably very poor. A direct correlation between the overall technical condition of a ship and an unnoticed "accidental anchoring" after the chain has slipped - especially over longer distances - can therefore also be ruled out as a generalised explanation.

If, on the other hand, it is assumed that it was Russian sabotage, further indications of a Russian connection should be included in the assessment. Because there is such evidence: the reconnaissance vessel Sibiryakov (85 m, 3000 t) equipped with submersibles had been in the area of the Balticconnector pipeline at least three times in 2023 and sailed along its north-south line. This happened exactly in the area that was damaged by the NewNew Polarbear a few weeks later. At the exact moment the ship crossed the pipeline in the early morning of 8 October 2023, it was in the company of the Russian icebreaking, nuclear-powered special cargo ship Sev morpu t. This ship can certainly be considered a state vessel, it belongs to the Russian state nuclear energy company Rosatom and has assisted in missile tests by the Russian Navy in the past. Michelle Wiese Bockmann from Lloyd's List Intelligence describes in an article from 27 December 2024 that the

Eagle S had even been used as a platform for signals intelligence (Sigint) in the past. According to the article, Sigint equipment had been installed on the ship in the past, and personnel had remained on board to operate this equipment. The article also states that the equipment was taken off the ship for analysis when it reached Russian harbours; it explicitly does not describe that this equipment is currently on board. When asked, Finnish authorities stated that they had not found any Sigint equipment. The veracity of the Lloyd's List Intelligence report cannot be verified at this time. However, the reputation of the publication and author as well as the general conditions may speak in favour of the thesis: Lloyd's is a renowned organisation, and the author has repeatedly attracted attention as an expert on the Russian shadow fleet. Moreover, the approach described is not new - Russian trawlers also went to sea in such a role during the Cold War. A study by Polish scientists at the University of Gdansk, published in March 2025, fits in with this topic. According to the study, GPS jamming in the Bay of Gdansk is apparently carried out by ships. It will be easy to check whether warships were in the sea area or whether merchant ships were also deployed here. If the report is accurate, this would be a strong indication of direct Russian state involvement in the Eagle S incident. No state actor would bring sigint material, personnel and documents onto a ship it does not control; the risk of loss or leakage of confidential information would be too high.

Russia again and again

The cases presented here are an unusual accumulation of "accident sequences" that are difficult to understand and not very plausible. Without exception, the ships involved have links to Russia and are possibly under Russian control. Other Russian ships with an assumed sovereign mandate also appear to be involved in the relevant processes.

The crews state that they did not notice the loss of the anchor. This is very unlikely according to our assessment, but it is theoretically possible. Let's assume it was. The captain overhears the loud rumbling of the anchor chain and initially does not realise that he is sailing with a dragging anchor. But when the ship sails like this for more than ten hours and several changes of watch and changes course and speed up to full circle, this argument becomes absurd. Someone must have done things on the bridge of the ships - or deliberately not done them. And if you go full circle, the sea behaviour of the ship changes significantly, "Look out, ship is coming across the sea!" is then often heard over the loudspeaker system on German ships. This cannot go unnoticed. The ships' movements, which can be traced with the help of the recorded AIS tracks, therefore cast considerable doubt on the theory of unsuspecting crews and ships travelling "automatically". And when you realise it, the captain's question should be: Why are we going full circle? But if you realise that you have (accidentally) lost your anchor, why do you continue sailing and damage your own ship and the infrastructure? Why not stop? Since changes in speed were recognisably possible in all cases, it cannot be claimed that control of the propulsion system was blocked and it was not possible to stop. Were signals given that the ship was unable to manoeuvre? Were calls for help made or at least the surrounding area warned? Was an attempt made to raise the anchor or cut the chain? Nothing like this has become known, nothing that would exonerate the crew from the accusation of wilful action. It has to be said so clearly: the ship's command must have known what they were doing and they obviously did nothing to avert damage. In a constitutional state, there is a presumption of innocence and, in case of doubt, a defendant must be acquitted. In all five cases described, however, there are strong indications that, in the context of an assessment of the evidence, speak in favour of gross negligence, if not intent. Taking into account the circumstances described here, it is very likely that the incidents are the result of deliberate action or omission. The Finnish chief investigator Risto Lohi expressly came to similar conclusions in the case of the Eagle S. Although the ship was released in March 2025, three men from the crew remain in custody.

State action is assessed according to different standards: The term hybrid warfare has become established for Russia's actions in recent years. Russia has repeatedly demonstrated activities directed against the West, from GPS jamming in the Baltic Sea to assassination attempts in various countries and the recent attacks with construction foam against cars in Germany or the attack on the waterworks on the island of Gotland. The list of incidents attributed to Russia is now very long. But what could be the motive for attacking cables and pipelines with the help of freighters right now? Russia sees itself in an existential conflict with the West and does not even rule out an open military escalation. Against this backdrop, the destruction of cables and pipelines could cause considerable damage and thus fuel uncertainty. Russia could also gain insights into the West's approach in such cases. Should there also be noticeable failures, this would make the governments involved look weak and call into question their ability to act. As the Baltic region cut itself off from the Russian electricity grid, of which it had been a part since Soviet times, on the morning of 8 February 2025, it is dependent on its connections to the European grid. Due to the destruction of the EstLink cable by the Eagle S, 750 megawatts of transmission capacity are currently missing. Russian state action could even be causally linked to decisions made by the Baltic states - but this must ultimately remain conjecture. Russia's alleged action of using ships to attack cables and pipelines has provoked various reactions. NATO has intensified its surveillance of European waters. The countries bordering the Baltic Sea are increasingly exchanging information. Authorities, but also social media, are closely monitoring the behaviour of ships in the Baltic Sea Deviations from normal behaviour are now quickly detected and reported. This can be seen in the increasing speed with which the neighbours have been able to react in recent cases. Another reaction is to step up inspections, for example when Denmark starts checking ships in the roadstead off Skagen. Further measures against the shadow fleet are being discussed in the EU. For example, environmental protection requirements and adequate insurance cover could be checked on tankers travelling through. It is also conceivable that penalties could be increased for all legally responsible parties - similar to terror offences - the ship could be arrested and all persons and companies involved could be banned from the EU. Complex considerations need to be made here, including with regard to a possible precedent effect under international (maritime) law. The very poor technical condition of many Russian ships in the Baltic Sea is documented. Controlling them is therefore in the interest of all neighbouring states, regardless of the political context, due to the threat of environmental damage. Only the flag state can complain, as it alone has sovereignty over its merchant ships.

Another development in connection with Russian shipping gives cause for concern. There are increasing indications of accidents on board that could have been caused by sabotage. In the last three months, five tankers travelling for Russia have been the victims of accidents. In two of these cases, it could have been an attack with limpet mines. This was reported by Reuters on 24 February, citing security sources. According to the report, Soviet-type BPM limpet mines were used, which are fitted with time fuses and delay times of up to one month. It is not yet possible to assess the facts of the case, but it shows that there may be a larger context in which Russia and other actors are operating.

The will to act is there among our partners in the Baltic Sea region. Germany should also offer itself as a "leaning power" here, as it is the only country bordering the Baltic Sea that has the infrastructure and personnel to provide comprehensive security in the maritime domain in the sense of a Baltic coordinator. With regard to the task of the Commander Task Force Baltic, close co-operation between the western Baltic Sea states is a given - if not the decisive prerequisite for this. What remains challenging in Germany is the diffusion of responsibility between the relevant authorities. And the armed forces are faced with a dilemma. We are trying to use military means to solve profoundly complex civilian problems. In this respect, the implementation of political will in official structures and tasks is required, especially in Germany. The German Navy has a role to play here: maritime surveillance, information exchange, administrative assistance with divers and underwater drones, analysing events and the command of such operations are already challenging us today.

As readers of marineforum, we can and should therefore contribute to the discussion so that our nautical expertise is heard. One of the aims of Russian information operations is to sow doubt: It is enough for Russia if we do not trust our own authorities; it does not even need to get us to adopt Moscow's view of things. We can and must all work against this. Let's look at the arguments and draw conclusions from them, then let's name the perpetrators, because it still applies: Crooks must be called crooks. Or, as Axel Stephenson wrote on marineforum.online/:

Letting an anchor weighing several tonnes slip or losing the entire anchor doesn't just happen - completely unintentionally, unnoticed and totally silently!

- any more than you would overlook "a battle tank on the market square in Osnabrück", to use the words of the Inspector of the Navy.

Alexander Rosemann