A new study aims to refute claims that offshore wind turbines pose a danger to migratory birds. The study concludes that birds fly around wind turbines and that the risk of collisions is significantly lower than previously assumed.

The study commissioned by the German Offshore Wind Energy Association (BWO) was carried out by the independent ecological research and consultancy firm BioConsult SH from Husum and aimed to determine the collision risks between migratory birds and wind farms in the North and Baltic Seas.

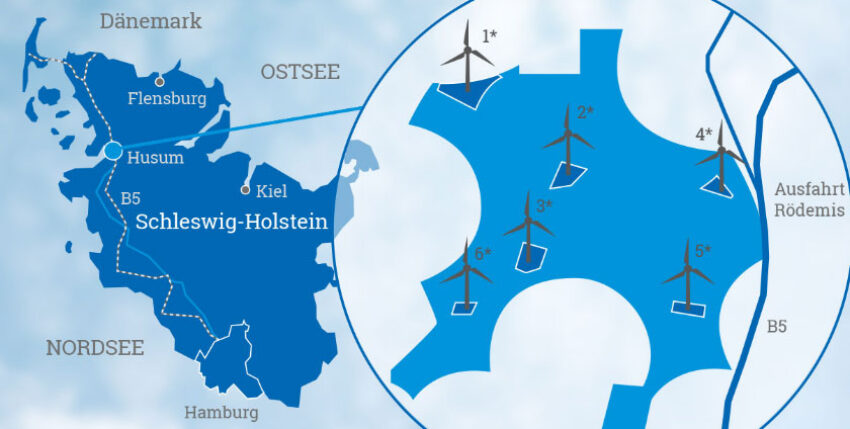

The study was conducted at the North Wind Test Field near Husum. It covers an area of around 150 hectares and currently comprises five wind turbines of different types and sizes. A sixth turbine is being planned. The flight paths of common bird species such as waders, geese, ducks, gulls and songbirds were analysed.

To understand the birds' movements, AI-controlled stereo camera systems were installed to record all bird and bat passages through the rotor plane both during the day and at night. Nocturnal activity was recorded using infrared cameras in combination with infrared emitters. A special bird radar, which was operated continuously throughout the study period, provided real-time monitoring of bird movements. This networked system made it possible to record flight movements in the area of the rotors with a very high degree of accuracy. This enabled the researchers to record and analyse the movement patterns of over 4 million birds in the period between February 2023 and November 2024.

This showed that practically all day- and night-migrating birds reliably flew around the wind turbines installed there. The avoidance rate was over 99.8 %. In addition, there was no statistical link between migration intensity and collision risk, i.e. the collision rate did not increase even when bird migration was high. The study therefore concludes that a blanket shutdown of wind turbines during the bird migration period is no longer a sensible approach. This conclusion was based on the results of the mortality surveys, which revealed a relatively low number of collision victims: Approximately 100 fatalities of all bird species, or about 0.0025 %, were recorded at the five monitored wind turbines during the study period. This corresponds to an average of around 13 collision victims per year and turbine.

The study comes at a time when Germany is driving growth in the renewable energy sector. By the end of 2024, a total of 1,639 turbines with an output of 9.2 GW had been installed in the country. Germany had set itself the target of increasing offshore wind capacity to 30 GW by 2030, 40 GW by 2035 and 70 GW by 2045. There is still a long way to go for all those responsible. This research should therefore improve the data basis and depoliticise the discussion so that future decisions are made on the basis of facts, according to the BWO's Managing Director.

Whether the study can make the discussion more rational remains to be seen. An environmentally compatible expansion of offshore wind energy must first clarify the political question of whether there must always be a balance between environmental protection, nature conservation and security of supply. And finally, the results of the study can only be applied to offshore turbines. This is because a further study is required to rule out the possibility of an increased risk of collision in situations where bird migration encounters other bird species and adverse weather conditions at sea. This could not be investigated in the test facility on land.

kdk, The Maritime Executive, Enercon