Mine warfare in the North Sea began with a modest operation in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71. The approach to Wilhelmshaven was secured by mine barriers to prevent French forces from entering, as a French squadron had previously briefly flown the flag at Helgoland. These barriers were then intensively guarded by the existing coastal defence units, but not a single French ship came anywhere near the restricted areas during the war.

After the war, the development of mines, at that time still combined with torpedoes, was further promoted, but without producing any spectacular activities. The first real sea mine, the model C 77, was put into service in 1877. It was an anchor mine with five lead-cap detonators and an explosive charge of 40 kilos. This mine remained an active weapon in the navy and was also used intensively at the beginning of the First World War. It can therefore be regarded as the forefather of German mine development. The successor types were then developed from this mine, the C 77 CA, C06, C05, Carbonit mine and, from 1912, the Einheitsmine A (EMA).

The Russian Empire also bought the C 77, rebuilt it and put the mine into service as the Model 1877. Somewhat later, after evaluating the use of mines in the Japanese-Russian War, Germany began to build up its mine defences from 1905 and equipped them with old torpedo boats that were no longer suitable for their original use, but which were still quite provisional and fitted with simple search equipment.

As in Germany, mining in Great Britain was a shadowy industry. Until the First World War, the stock of mines here mainly comprised British Elia mines, a replica based on the Italian Elia mine and the MK I anchor mines developed in-house. The firing mechanism was based either on lead-cap shock fuses according to the Hertzhorn principle or on ignition by lever arms, i.e. mechanical ignition triggering.

In 1918, the first 472 bottom mines developed by England were deployed. They were laid by the 20th Destroyer Flotilla off the Belgian coast. Equipped with a magnetic detonation system, the mine detonated around 450 kilos of explosives. However, this type of mine was very unreliable, with around 60 per cent of the minelayers reporting single detonations immediately after the mine was thrown or shortly afterwards.

However, at the beginning of the war in 1914, Germany immediately used the mine as an offensive and defensive weapon. The Ems and the Borkum area were secured with barriers, as was the Jade with the approach to Wilhelmshaven. The Elbe estuary was also blocked with mines in the Cuxhaven area. These barriers were repeatedly redesigned during the war, as ice drifts in winter caused numerous mines to detonate. But the tidal currents also drove mines away or tore them loose from the anchors. Numerous drifting mines and landings of mines on the beaches bear witness to this. As in 1870/71, no enemy ships appeared in or in front of these barriers; they only hindered their own forces. Mines and a barrage meant that the Jade was only passable for the capital ships with pilots and at high tide. However, the running aground of the armoured cruiser Yorck on the Jade barrage and the effect of the mines, which led to the sinking of the ship with a high loss of personnel, demonstrate the effectiveness of the system.

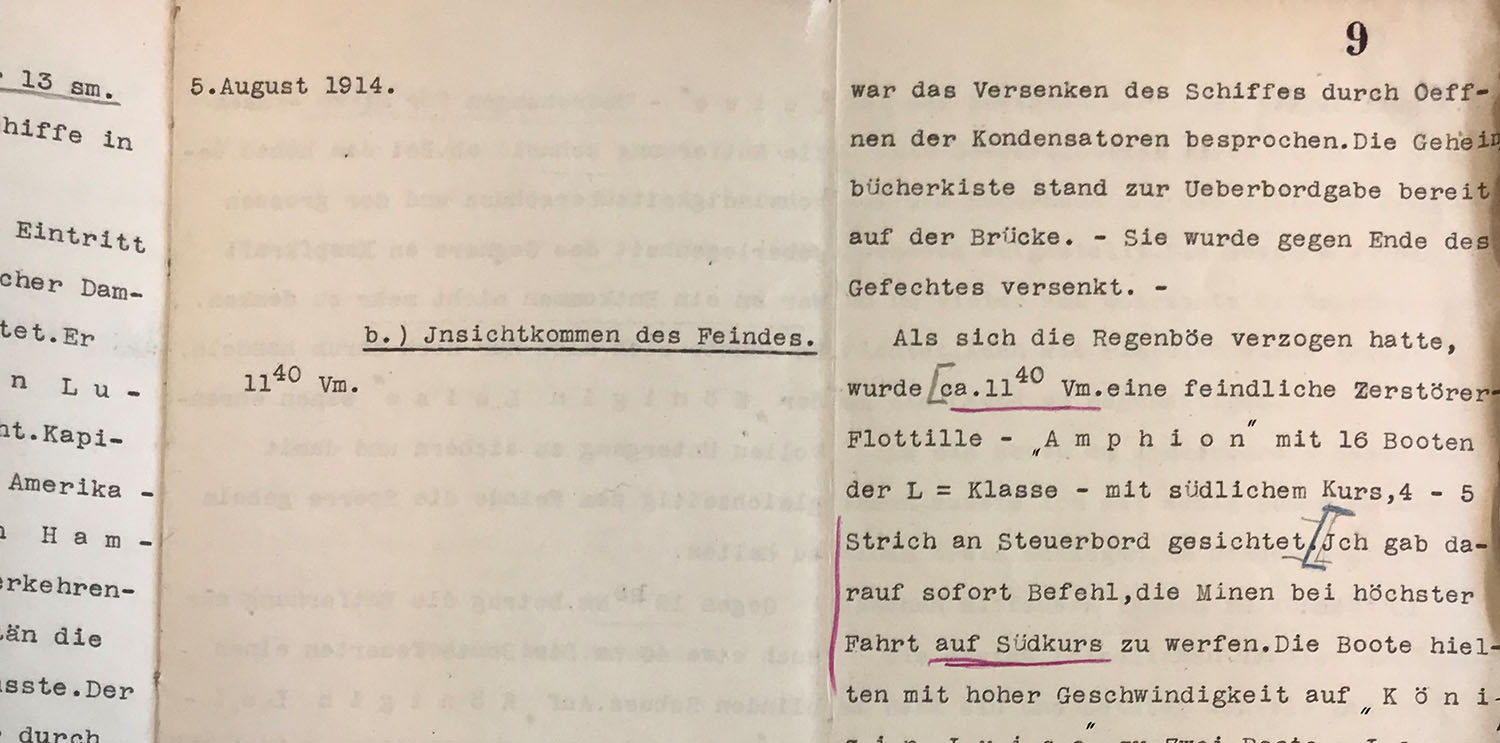

The barrage thrown off the Thames by the civilian ferry steamer Königin Luise, which had been hastily converted into the auxiliary cruiser SMS Königin Luise, became an offensive mine barrage. The unfinished minelayer, armed only with two 3.7-centimetre revolver guns, was loaded with anchor mines and set sail on 4 August 1914. Off the Thames estuary, the Königin Luise was expected on 5 August by the small cruiser HMS Amphion and 16 destroyers, was able to lay the barrage unnoticed by the enemy and sank herself in an unequal battle with the destroyers. Some of the crew were rescued by the British ships, but gave no information about the mine laying. Unaware of the mine-laying, the Amphion ran aground on one of the mines and sank.

Mine defence also began with the use of mines. In the absence of suitable minesweepers, auxiliary minesweepers were used. These were fishing vessels whose design made them suitable for carrying and deploying search lines and towed gear. The Imperial Navy now increasingly used older torpedo boats that had been converted for mine detection and clearance. At the same time, development work began on a minesweeper. This resulted in the M 1916 class, a compact vessel, well armed, seaworthy and capable of carrying the usual mine-clearing equipment. For the shallow sea area off the coast of Flanders, the FM boats were developed as a class with a shallow draught. Some of the smaller A-class torpedo boats were also equipped with minesweeping equipment and were used for clearing tasks. The naval airships proved to be a very good aid for reconnaissance of the mine barriers. With good visibility, they were able to recognise the rows of laid anchor mines, determine their positions relatively accurately and thus guide the minesweeping units to the barriers. England also further developed its minesweeping forces and introduced a new clearing device equipped with paravanes under great secrecy. This device was based on the same principle as the German minesweeper with otters.

Gradually, mine laying and mine sweeping spread to the entire North Sea, which was soon criss-crossed by a dense network of German and British mines. While the British initially used converted ferries, the Admiralty very quickly switched to small cruisers and destroyers. Examples include HMS Abdiel, HMS Telemachus and HMS Vanoc.

The mine war in the North Sea intensified month by month. By the end of the First World War in November 1918, 95,899 mines had been laid by Britain in the North Sea. In addition, a further 69,685 anchor mines were laid by British and American ships in the Northern Barrage between the Orkney Islands and Norway to seal off the North Sea. This barrage was intended to reduce submarine activity, but in fact only six German submarines were lost in the barrage.

The Imperial Navy also laid mines off the English coast to block the coastal routes around England. Mines were also laid off the Belgian coast to secure the approaches to Oostende and Zeebrugge against enemy advances. As there was a lack of well-armed and fast minelayers in Germany, the idea of laying mines with submarines was met with great interest. One line of development led to the construction of minelaying submarines. These small UC boats were to lay mines off England from Flanders for the first time. After the initial successes, the UC II and UC III classes were developed, which were now considerably larger and had a greater range. Initially twelve, later 18 anchor mines of the UC type could be stored in shafts, transported and deployed. The boats also carried three torpedo tubes and an 8.8-centimetre gun. The UC mine was a slightly modified EMA anchor mine that was redesigned for use from a submarine and contained up to 200 kilograms of explosives. This type of submarine had proved its worth in the North Sea and the waters around the British Isles, but also suffered a high loss rate.

Another development was the TeKa mine, an anchor mine that could be laid through the 53.3-centimetre torpedo tube. The mine development was very positive, but unfortunately the ejection system was not ready for use so quickly. The first TeKa mines were therefore deployed by aircraft in the Baltic in 1917. In addition to the UC boats, various submarines of other classes were equipped for mine laying and also deployed. However, their operational area was not necessarily the North Sea, but rather the west coast of England and the American coast. The Imperial Navy's records show that around 26,000 mines were laid by minelayers, auxiliary cruisers and submarines in the North Sea.

However, all of the anchor buoys in the North Sea had a huge problem. The design of the anchor chair and anchor line at the time was not up to the tides and weather conditions of the North Sea. Many mines broke loose and drifted first through the sea and then onto the beaches. It is not known exactly how many ships and fishing boats were sunk by these mines. It is therefore still not possible to determine exactly how many warships, merchant ships and fishing vessels were actually sunk by mines in the North Sea during the First World War.

On 1 September 1939, the Kriegsmarine was involved in various operational tasks. The Graf Spee armoured ship was operating in the Atlantic, the few submarines were in their operational areas and the focus of combat operations was in the Bay of Gdansk. There were no pure minelayers; the mine-laying capacity of the small cruisers, destroyers, torpedo boats, M-boats and speedboats had to be utilised. However, ferries, bathing steamers and the ships of the East Prussian Naval Service were suitable for laying mines and were converted into minelayers by the Kriegsmarine. With the declaration of war by England and France on 3 September, the navy now also faced a war on two fronts. The mine, in this case mainly the anchor mine, was an important and quickly deployable factor and was utilised accordingly.

All available mine-laying units were deployed to create the Westwall minefield, which initially consisted of 15 individual mine barriers. To the north of the mine warning area, the barriers in the area of the Große Fischerbank were then added, while in the area to the west and north of Heligoland further protective barriers were laid to secure the German Bight. These fields were part of the defensive barriers that were set up to protect German waters.

Very soon, however, the mine was also carried to the British coastal zone. This is where the destroyers, which could carry up to 60 mines, came into play. Due to their high speed and powerful armament, this type of ship was ideally suited for these offensive tasks. During the mine-laying operations off England, the destroyers had to pass through the Westwall barrier. For this purpose, a gap was planned between the individual barriers, which, with precise navigation, could be passed without danger. When the mine-laying destroyers sighted numerous fishing trawlers on the Dogger Bank in February 1940, Operation Viking was planned. Six destroyers were to pick up as many trawlers as possible and take them to Germany. The operation got underway and the destroyers were already in the interdiction gap in the southern part of the Siegfried Line when Z 1 Leberecht Maass was attacked by a German HE-111 bomber from KG 26, hit with 50-kilo bombs and hit. This mistake was due to communication difficulties between the naval command and the Luftwaffe command. Neither the ships on the ground nor the aircraft in the air were aware that both branches of the armed forces were operating in this area.

During the evasive manoeuvre following the attack on Z 1, Z 3 Max Schultz hit a presumably British anchor mine, which came from the British barrage ID 1 laid on the night of 10 January 1940. This barrage, consisting of 120 MK XIV/XV anchor mines, now lay in the barrage gap.

The Max Schultz sank with its entire crew. Z 1 also sank, but some of the crew could be rescued. With the loss of these two destroyers and the other destroyers and small cruisers sunk in the Norway operation, the mine-laying capacity was considerably reduced. After France was also occupied, mine-laying capability and barrage laying could be increased again, as speedboats, minesweepers, clearing boats and torpedo boats now had much shorter approach routes to British waters. All these units were now used to lay mines, even though some of them could only carry six mines per boat.

The trials for an air-dropped mine were completed as early as 1932, so that the so-called Luftmine A (LMA) was ready for series production. This was followed by the much larger LMB. Both were base mines that were detonated by magnetic induction. Other aircraft-borne mines followed, such as the LMF and the BM series of bomb mines. German fighter planes could carry and drop up to two mines. The Luftwaffe also began using mines against England, dropping at least 1,500 mines, but unfortunately not in the coordinated way that the British later did. Two LMAs were found in the Thames at low tide in November 1939 and were successfully defused and analysed. This meant that England knew the fuse system of the mines and was able to develop appropriate systems for mine defence. The LMA, LMB and BM series mines were also delivered to the troops. The BM was developed from bombs, in which a fuse system was installed for use at sea to trigger when a ship overran. At the same time, the Luftwaffe used the LMA, LMB and BM for bombing British cities. Here, too, there were the usual number of unexploded bombs, which were thoroughly examined after defusing. Although it was strictly forbidden to use certain detonation systems in these "bombs" for use at sea, it is not clear from the documents available in the Federal Archives whether this instruction was strictly adhered to. However, the LMA, LMB and BM series base mines could also be brought into the operational area and thrown from surface vessels after minor modifications such as removing the parachute and storing them on a launcher. This was used intensively after the Luftwaffe was no longer able to adequately fulfil the airborne minefield requirements.

From 1944 and the successful Allied landing on the mainland on 6 June, another type of mine was introduced and deployed, the coastal mine A (KMA). A 75-kilo explosive charge was installed in a concrete base, which was triggered by a Hertz horn on a 1.75 metre high iron tripod. This mine was developed to defend against landing units on beaches and was deployed in the coastal area of the Netherlands, the offshore West, East and North Frisian islands and the west coast of Denmark with at least 27,996 examples.

The last mine barrages from the German side were dropped in and off the German North Sea harbours and on the Weser just before the end of the war and consisted of the bottom mines still stored in the depots. The Royal Navy also relied on the tried and tested anchor mines and continued to develop them after the First World War. The detonation systems were improved; in addition to contact detonators, acoustic and magnetic induction detonation systems were also used. The charge weight of the anchor mines was up to 225 kilos. These mines were used to create barrage fields along the entire east coast of England, to secure shipping lanes and also to lay the English Channel barriers as in the First World War. Mines were also developed that could be carried by submarines. Surface vessels, mainly destroyers and minelayers of the Abdiel class, again bore the main burden of mine-laying operations, but submarines were also used for this purpose. As the German mine warning area was known, operations were now also carried out to close the gaps and obstruct German shipping in the German Bight. A total of 57,780 mines were dropped by England in the North Sea. One mine-laying operation ended in tragedy on 31 August 1940, when five British destroyers were tasked with laying the CBX5 barrier. In the process, the destroyers ran into a mine barrage, HMS Esk and HMS Ivanhoe sank and the destroyer HMS Express had its forecastle torn away almost up to the bridge superstructure.

Despite this loss, the Admiralty continued the mine warfare. As the occupation of France meant that smaller units of the Royal Navy now also had the opportunity to bring mines into the waters controlled by the enemy, this chance was quickly utilised. The Royal Navy now deployed the Coastal Forces Crafts such as MLs Fairmile B, motor torpedo boats Fairmile D, as well as MTBs and MGBs as minelayers for coastal waters, i.e. the corresponding counterparts to the German speedboats. These boats could transport and lay up to four bottom mines or a maximum of ten anchor mines. These operations continued with varying degrees of success until almost the end of the war.

In addition to the laying of mine barriers by surface vessels, Great Britain also developed mine laying from the air, similar to what the Luftwaffe was already doing. The development of ground mines for these purposes began with the Mine A MK I to IV. These mines, with magnetic, acoustic or a combination of the two, were used until spring 1944. With a total weight of not quite 1,000 kilos, it was a relatively heavy mine. The A MK V was deployed with about half the weight. From 1944, the A MK VI entered service as the successor model to the A MK I to IV, while the lighter A MK VII was the successor to the A MK V. A MK VIII and A MK IX mines were also developed and deployed.

Like the German aircraft, the British bombers available in 1939/40 could only carry one or two mines. As the war progressed and four-engined bombers such as the Halifax, Stirling and Lancester were deployed, up to six mines could be deployed. In the "Gardens" along the Danish, German and Dutch coasts, 18,524 mines were dropped by the aircraft of Bomber Command and Coastal Command between April 1940 and the end of the war. The restriction to the coastal area is due to the fact that the forced routes of the Kriegsmarine led through it. These forced routes were searched for mines as thoroughly as possible with the existing mine detection, mine clearance and security forces and were considered a reasonably safe route. Searching and securing the open North Sea was simply not possible due to a lack of capacity. A total of 349 ships in the North Sea ran aground on these English mines, sank or were severely damaged. The development of the use of mines meant that mine defence had to be constantly changed and adapted. As mine defence also has a comprehensive scope, this area will be described in a later article.

Captain Lieutenant (ret.) Uwe Wichert is a consultant in military-historical research for MELUND, BLANO Expertenkreis Munition im Meer, Helcom and North Sea Wrecks.

Photos: Archive author

One Response

Commentary from Flanders (Researcher Imperial Navy) :

In WW1 the majority of the Flemish fishing fleet had fled: partly to NL (Zierikzee), partly to GB.

NL or GB : was determined by the weather and wind direction (sailing ships).

In the UK, only a fish entry licence could be obtained for the coastal zone that was mined. The English fishermen were allowed to work in the mine-free zone.

The fishermen's wives had to work in the munitions factories and after the war they came back with a "yellow" skin.

So, the British were not friendly to the allies from the EU mainland....