The Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency plays a key role in ensuring safety in German waters. Divers from the authority search for underwater obstacles in the Elbe.

On the Elbe, between Hamburg and the estuary. A northern German autumn day, the water is grey-brown, sometimes it rains. Large ships pass by, heading for the Hanseatic city or the North Sea. A boat rocks on the waves, "Ruden" is written on the bow. Three hoses in blue, yellow and orange, wound around each other in a spiral, lead from the boat into the depths. They lead down to Tjark Lange. The diver is travelling towards the bottom.

The blue hose is used for breathing. The compressed air flows through it from the cylinders on the "Ruden" down to Lange. The orange-coloured hose enables communication. Thanks to it, Lange's breathing can be heard in the cabin of the "Ruden". And also his voice, a little tinny, as he announces: "Diver on the bottom". Over the next few minutes, the 35-year-old from Schleswig-Holstein will be diving along the bottom of the Elbe at a depth of around 20 metres, feeling for unknown objects. Groping, because he is almost blind despite two lamps on his helmet. He can only see a few centimetres in the murky river. He holds on to a line that connects him to the anchor weight of the "Ruden". This gives him orientation. Lange will use the yellow hose to sound the depths and try to identify what he finds down there. These are his tasks as a wreck diver from the "Atair".

Meanwhile, the "Atair" is anchored a few stone's throw away. She is the mother ship of the "Ruden". 75 metres long and equipped with modern technology, the "Atair" bears the federal eagle. It is an official survey, wreck search and research vessel costing over 110 million euros and is the largest in Germany.

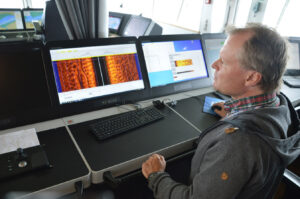

Its captain is Ulrich Klüber, who is in command in a shirt and jumper instead of a uniform. In the days surrounding Tjark Lange's mission in the Elbe, Klüber explains in his calm and precise manner what the "Atair" and its crew of almost 20 are doing. He explains it on the bridge, where nautical charts, monitors and large windows provide an overview.

"The 'Atair' is currently being used to search for wrecks," says Klüber. What kind of wrecks, are we talking about sunken pirate ships with gold treasure? No, the "Atair" has not yet found any gold, admits Klüber. But the oldest wrecks are "some old sailing ships", "could well be something from the Middle Ages". There are cases, the captain recalls a find with a turned wooden railing, "where you can really let your imagination wander". The database of the Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH), whose flagship is the "Atair", lists two and a half thousand wrecks and other underwater obstacles.

The ships may be more recent or even have been stuck in the sediment for centuries and come out again due to the dynamics of the water. The problem in tidal waters such as the German North Sea coast is "that objects silt up and are washed free again," says Klüber.

The "Atair" also helps track down individual ship parts such as anchors or cargo. For example, containers that the giant freighter "MSC Zoe" lost in a spectacular accident in the North Sea at the beginning of 2019.

If the ship has discovered something or checked a known underwater obstacle, the official nautical chart can be updated. An abbreviation for "wreck" or other "obstacle" is noted at the relevant position, together with the shallowest depth. This allows other ships to steer clear of the wreck if necessary so that they do not touch it, anchor there or have their fishing net torn. If the obstacle is too dangerous, it can also be salvaged.

The "Atair" is equipped to detect wrecks, containers and the like. It has two types of plumb bobs and a side-scan sonar. The devices emit acoustic signals and pick them up. These are used to generate images that appear on monitors on the bridge during the wreck search. For example, one that shows an underwater landscape glowing from orange to rust-red, covered with a grid pattern. "We're heading towards the red line now," remarks Klüber as the "Atair" approaches the suspicious spot in the Elbe at the mouth of the Oste.

The ship is travelling at around five knots. The slower, the better the underwater images. Like other crew members, Klüber has dual training. He not only has a captain's licence, but also a degree in surveying engineering and can therefore interpret the images. Sometimes you can see stones and ripples of sand, he judges, then he realises: "There's something there." What it is remains unclear, even after the "Atair" has turned round and headed for the elongated, hilly object again. "You can't always assume a ship shape from the wreck, it could also be individual pieces of debris," explains Klüber.

In the meantime, Tjark Lange has come to the bridge. The man with the reddish beard comes from Krempdorf in the district of Steinburg and trained as a diver at the Stuttgart Waterways and Shipping Office, initially working on the Neckar. The diving crew also includes Martin Sulanke (61) from Bad Schwartau, who has been a professional diver for 36 years, and Jan Lütjen from Stade; 46-year-old Lütjen used to go to sea as a naval barrage weapon mechanic (Olpenitz base). Lange discusses the matter with the captain: the diver should get to the bottom of the find. Perhaps he can recognise what it is. And sound the highest point. If it was a thin mast, for example, the modern equipment might have missed it.

So in the afternoon, Lange descends from the dinghy "Ruden" to the bottom of the Elbe. He remains connected to the upper world through the coloured hoses for air, communication and sounding. "Diver on the bottom," he finally says.

Over the next few minutes, information and impressions emerge alongside the sounds of breathing: "sandy ground", "ah, I've got something...", "here comes something even bigger", "this is the part we were looking for", "feels like a ship".

Sulanke answers him upstairs. They agree to sound at several points. Another sailor sends air down through the hose, the end of which Lange holds in his hand. The depth can be determined based on the pressure. "Yes, air is coming," confirms the diver.

Finally, Lange is back at the top of the "Ruden". The rain has stopped, but his white-blonde hair still looks damp. The water was warm, he realises. The neoprene of the suit is around half a centimetre thick and the equipment is heavy. He has now taken off his helmet and can take a deep breath in the autumn air. Everything went well again. If not: Lütjen, who is now joking around with Lange and putting his arm on his shoulder for a photo, had stood ready in almost finished gear. To dive down if something happened to Lange. You have to be able to rely on your colleagues 100 per cent, says Lütjen on another occasion, "and you can". For today, however, the job of the wreck divers from the "Atair" is done.

A report is written later. The captain states that the shallowest depth at the site investigated is 16.43 metres. According to the report, it could be the remains of a wooden ship. But what exactly the wreck searchers from the "Atair" were dealing with remains hidden on this autumn day in the murky waters of the Elbe.

Phillipp Steiner