Australian iron ore magnate Andrew Forrest has joined the call for a moratorium on deep sea mining, adding his non-profit group to the growing list of organisations opposing the practice.

In his speech at the COP27 conference in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, Mr Forrest echoed the concerns of many marine biologists and conservationists who believe that deep-sea mining could cause ecological damage and even the extinction of the near-bottom environment.

"The deep seafloor is one of the least understood ecosystems on the planet. It is critical to ecological processes that affect our entire ocean, and yet our scientific knowledge of it remains extremely limited," said Forrest.

Deep Sea Mining

The idea of mining the deep seabed for minerals is not new, but it is currently approaching commercialisation. The Swiss shipping company Allseas carried out the first test of its deep-sea manganese nodule collection system just last month. And if all goes according to plan, it will begin mining the nodules from the seabed in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, located in international waters southeast of Hawaii. According to the mining company "The Metals Company", the lease area is home to the world's largest undeveloped nickel deposit, and the nodules also contain cobalt, manganese and copper. However, the contractor first needs official authorisation. However, the International Seabed Authority is only now laying down the rules with the aim of establishing legal deadlines by 2023.

Unknown effects and lasting consequences

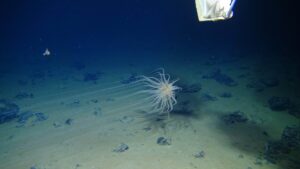

The environment on the seabed in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone has been little researched. Scientific studies of the area often discover new species - sometimes dozens of them in one go. Critics of deep-sea mining warn that the potential impacts of mining are still unknown and are likely to be harmful to local species. These include so-called sediment plumes created during mining that cover neighbouring areas, as well as toxins released into the water column by mining waste and the destruction of habitats caused by the removal of the nodules themselves. As the nodules form on a timeline measured in millions of years, the physical alteration of the seabed must be effectively permanent. Some species, such as the hard-to-classify sea anemones, for example, rely on the nodules as anchor points in an otherwise featureless deep-sea plain.

Good examples

BMW, Volvo, Samsung and Google have already pledged not to source metals from deep sea mining. Now Forrest, as head of Fortescue Metals, has also added his name to the list of refuseniks. He compared the regulations that his mining company has to fulfil on land with the regulations for the international seabed and suggested tightening the latter.

"If regulators can't apply the exact same cross-ecosystem studies of flora, fauna, terrain and unintended consequences, and can't set the same or higher standards as on land, then the seabed should not be mined," Forrest said.

Videos for the visualisation of deep-sea mining

Source: Deepwave - the marine conservation organisation, maritime-executive.com

One Response

It is no wonder that the Australian iron ore magnate A. Forrest is negative about the upcoming deep sea mining, as this could become a competitor to large-scale, particularly environmentally destructive mining in Australia. Moreover, China is the dominant supplier of the most important industrial metals. For Germany in particular, China is the largest supplier of 45 different minerals, without which neither the automotive, mechanical engineering and defence industries in Germany nor the energy transition and decarbonisation of the economy and society would be possible. It is therefore fitting that Germany has acquired two exploration licences from the UN International Seabed Authority (ISA) since 2005 as a precautionary measure - one in the Pacific for manganese nodules and one in the Indian Ocean for sulphides, each with high-quality discoveries of cobalt, nickel, copper, manganese and rare earths. The deep-sea mining that is expected in the future brings opportunities for the fourth-largest industrialised nation in three respects:

Firstly, by signalling to these supplier countries that there are alternatives to land-based mining - one of the biggest environmental destroyers in the world - Germany can free itself from its over-dependence on key metals from the seabed.

Secondly, German technology can be used to realise environmentally friendly marine mining and find new sales markets and cooperation with foreign partners, e.g. in their exclusive economic zones. The marine mining equipment from Bauer Maschinen GmbH in Bavaria, which is financially supported by the BMWK, has just won an important innovation award.

Thirdly, the Berlin ministries should actively seize the opportunity to anchor German and European environmental standards in the new sector of deep-sea mining internationally, and not leave this important aspect to others by retreating and the recent press statement by the BMWK and BMU that Germany wants to take a fearful "preemptive pause" on deep-sea mining.

It is always surprising that the options of marine mining are not recognised in German offices and party offices - not in the BDI, not in the automotive industry, not in the media and not in society

says Uwe Jenisch, Kiel