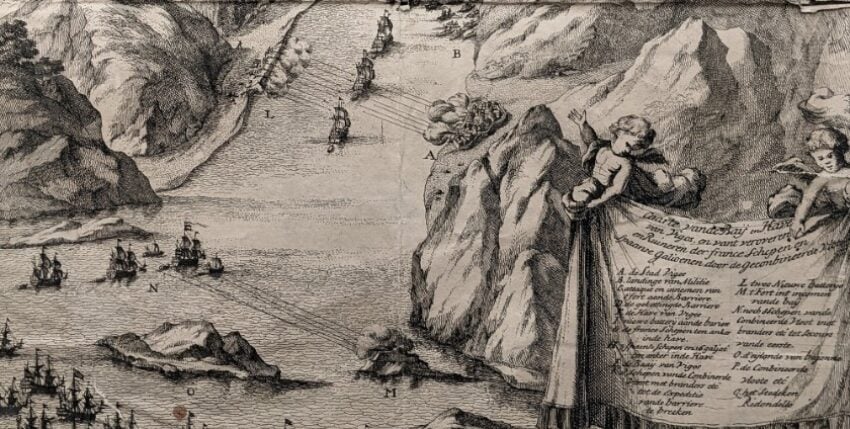

It was one of the biggest coups in the War of the Spanish Succession. The British admiral Sir George Rooke had actually intended to conquer the harbour city of Cádiz as a naval base on the Iberian Peninsula in September 1702 with an Anglo-Dutch fleet, but failed due to disciplinary and tactical problems with his landing venture. When he was already on his way home, news reached him in mid-October that the Spanish silver fleet under the command of Manuel de Velasco y Tejada, coming from Havana and actually destined for Cádiz, had entered the Bay of Vigo with French escorts. For Rooke, it was a unique opportunity. Persuaded by the commander-in-chief of the Dutch squadron, Admiral Lieutenant Philipp van Almonde, to launch a surprise attack, they sailed together towards the Galician coast. However, they were late. The Spanish had already had some of their precious cargo unloaded and taken away, but a captured monk told them that most of the silver was still on board the Spanish galleons. So Rooke had the bay scouted so that he and his Dutch allies could enter the Ria de Vigo on the evening of 22 October 1702. Although the invaders came under fire from the surrounding fortresses and access to the Spanish treasure ships in the harbour of Redondela was blocked by a boom with a gun battery, the attackers were not deterred. After a consultation on board the flagship ROYAL SOVEREIGN, Rooke decided to forego a classic line battle due to the cramped conditions and instead send out a detachment of fifteen English and ten Dutch battleships with all fire ships to attack - a tactic that would prove its worth a few hours later.

The attack began in the early morning of 23 October 1702. It was initiated by Vice-Admiral Thomas Hopsonn with a ramming attack by his flagship TORBAY on the outrigger in question. However, the enemy had not remained idle in the meantime. The commander of the French squadron, Admiral François-Louis Rousselet de Château-Renault, had positioned powerful warships at both ends and inside the barrier, covering the entrance with their broadside. Another threat came from Fort Rande at the southern end of the bay, where a gun battery also targeted the attackers. In total, the Spanish fortifications were equipped with more than 30 cannons, but they managed to neutralise them with the help of a landing party from the Duke of Ormonde that had joined them in the meantime. Vice-Admiral Hopsonn, however, was less fortunate. Although his flagship managed to break through the enemy's outrigger, unfavourable wind conditions prevented further English and Dutch ships from following and drove the TORBAY into the middle of the French squadron. Nevertheless, the battle ended with an overwhelming victory for the British-Dutch alliance. The Spanish lost all but five vessels captured by the enemy, including three galleons and several frigates, lightships and transports. For the French, the defeat was a real disaster, and one with political consequences. Of their 15 ships of the line, two frigates and one lightship, five were captured and the rest were either destroyed by the enemy or by the French themselves. Added to this were the high losses among the crews. While England and the United Netherlands suffered around 800 casualties, 2000 men were killed on the other side.

The victory at Vigo strengthened England's reputation as a naval power and played a decisive role in the Portuguese, formerly allied with France, joining the Grand Alliance in 1703 with the signing of the Treaty of Methuen. However, the victors' joy over the captured treasures was limited. As the Spanish had already had a large part of the silver, worth around three million pounds, transported inland before the battle, the British were only left with a modest share worth around 14,000 pounds. Whether and how much silver sank to the bottom of the sea during the Battle of Vigo is not known. Investigations in this regard have been carried out several times by government agencies and private individuals, sometimes with minor successes. In the 19th century, for example, an English expedition succeeded in using a diving bell to fish not only a few rusty cannonballs but also a small amount of silver from the sea. Other treasure hunters, such as the American Vigo Bay Treasure Company, came up empty-handed despite their great ambitions. Whether there really is such a thing as treasure in the silver lake in Vigo Bay remains a mystery. One that may never be solved.

Andreas von Klewitz studied Slavic Studies and Eastern and Southern European History and is a freelance journalist

Andreas von Klewitz