Pooling and sharing is the new buzzword when talking about Europe, security and the budget. It should be clear to everyone involved that there will be no more "business as usual" in the sense of sole national provision in the future. It is worth looking at the bigger picture, as there is already some interesting military and security-related cooperation in Europe. Limited budgets and common interests unleash creativity and create new structures in Europe. Could the big players learn from the small ones?

Kai Schönfeld is an active naval officer and operator of the blog Networked security. On Understanding the sea Schönfeld writes exclusively about the security policy networking and cooperation between the navies of Belgium and the Netherlands:

In the current debt crisis, the defence policy of European countries is more divided than ever. On the one hand, there are calls for a common European security and defence policy in order to create more cooperation and save resources in national defence budgets. On the other hand, most political decisions remain within the narrow framework of individual national interests. The CSDP has so far proved to be an inconsistent patchwork of individual bilateral projects, temporary multilateral manoeuvres and missions as well as various other one-dimensional approaches and initial steps, which sometimes get lost in redundant double structures between the EU and NATO.

The following is an example of the co-operation between the Belgian and Dutch Marine be considered in more detail. Luxembourg's financial commitment in this context is not considered further. This co-operation is an outstanding example of a small but functioning regional co-operation that has established itself and proven itself in recent years. The aim is to clarify whether this project can serve as a model for other European projects or whether it is rather an exceptional structural phenomenon that cannot be compared.

The cornerstone of maritime co-operation between Belgium and the

The Netherlands was once involved in joint NATO tasks for the defence of the English Channel since the 1950s. Further treaties on joint training projects and supply services have been ratified since the 1970s. The hitherto loose cooperation turned out to be extremely dynamic and promising and continuously intensified, so that in the mid-1990s there was finally an enormous acceleration in the expansion of the joint projects. The "Admiral Benelux" and a joint naval command were also set up in Den Helder for peacetime. Towards the end of the 1990s, Belgium increasingly feared that it would not be able to maintain its maritime capacities; the Dutch were also looking for ways to work more resource-efficiently.

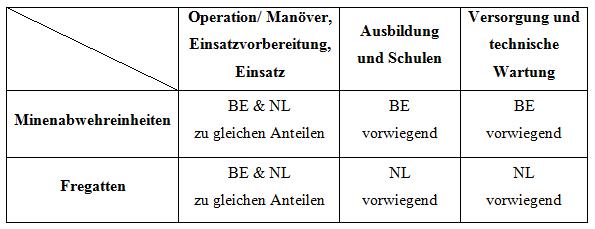

Two main co-operations ultimately led to the situation that prevails today: in 2007 and 2008, the Belgians acquired two Dutch Frigates of the Karel Doorman class. In addition, the Tripartite-class mine defence vehicles of both classes were built jointly in a binational project. Marines was modernised between 2006 and 2010. From then on, various core competences were shared. Today, this results in equal cooperation in six main areas of the fleets, which can be visualised in the following matrix according to Pieter-Jan Parrein:

Marine co-operation according to Parrein. Own graphic.

In a nutshell, this means a clear division of responsibilities and

Specialisation in core functions in the two Marines while at the same time reducing redundant structures. Belgium specialises in tasks in and around mine countermeasures; the Netherlands takes care of the Frigates; both share areas of responsibility and perform services for their own fleet and that of the neighbouring state. Institutionally, in addition to the joint naval command in Den Helder, this is reflected, for example, in the creation of the Belgian-Nederlands Competentiecentrum Support Departement Catering or the Nederlands-Belgian Operationele School, which is run and attended by naval personnel from both nations. At a tactical level, there are plenty of joint formations, manoeuvres and exercises and a high density of agreements and joint decision-making.

The success and efficiency of this binational naval structure is emphasised without any ifs or buts both in politics and in the fleets of the two countries. It saves resources, utilises synergy effects and contributes to the European idea on a normative level. The direction in which this co-operation was made possible is significant. The roots of this project do not lie in Brussels, not even in the Netherlands or the Netherlands. Belgian Parliament or in the cabinets, it was conceived. It originates from the fleet, is based on direct experience and is characterised by pragmatism, maritime expertise and the will of the Belgian and Dutch naval officers to work together. In my opinion, this is where the opportunity for a common European defence lies.

Particular national interests still deny a common European defence that could be centrally planned and implemented in Brussels or elsewhere. We need to pave the way in this direction. With local bi- or multinational co-operation, as outlined here, a gradual approach to the ideal of CSDP seems promising in the long term. Local security interests, which certainly differ in the EU area, could be taken into account in this way. The question is, however, whether such cooperation really works and can be established in the long term. In the BelgianAs a result of the Dutch-Dutch cooperation, it cannot be assumed that the two fleets have an internal balance of power. Nevertheless, one partner does not outvote the other, as sufficient autonomy has been created due to functional divisions. Similar projects, however, such as in the Baltic region or between Great Britain and France, have proved less successful, stalled or were not designed to last. Overall, however, it should be noted that bilateral relations, particularly in the area of defence, should not be forgotten in favour of a central EU policy. An interplay of small, localised and functionally balanced projects that work efficiently and sustainably could result in further positive developments for Europe. The question remains as to where Germany, as a geographically central state and leading demographic and economic power in Europe, could extend its feelers. There are probably both opportunities and risks here among the neighbouring states.

Links to the topic:

- BISCOP, Sven: Permanent structured cooperation and the Future of ESDP, Egmont Paper 20, Ghent 2008. PDF

- CONSTANTINESCU, Maria: Approaches to European Union military collaboration in the current economic austerity environment, in: Journal of Defense Resources Management, Volume 3, Issue 1 (4), April 2012, pp. 87-92. PDF

- PARREIN, Pieter-Jan: Some Ideas for European Defence Cooperation from the Case Study of the Belgian-Dutch Navy Cooperation, Royal High Institute for Defence Centre for Security and Defence Studies, Focus Paper 25, December 2010. PDF

- SAUER, Tom: Military co-operation in the European Union. Case: Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, IIEB Working Paper 15, Leeuven 2005. PDF

- ZUIDERWIJK, Rob L.: Maritieme visie. De Koninklijke marine in 2030. Voor veiligheid op en vanuit zee, Den Helder 2009. PDF

3 responses

For me, this is also a good example of cooperation that works, or more than that. Incidentally, the Dutch are an example of how it is possible to dispense with capacities altogether, see the discontinuation of the MPA component. Not entirely voluntarily, however, but out of financial necessity. When I used to talk about 'burden-sharing' within NATO and the possibility of dispensing with individual components during my time in active service, I was always met with outright disapproval, especially from the 'staff wranglers' in the 'policy' area. I am still of the opinion that you don't have to be able or want to do everything yourself.......but that requires a change in thinking. Some can do this better, others can do that.... For me, a good example of maritime grandstanding is Italy with its 'Giuseppe Garibaldi', half the Italian navy is lying on the floor because of this ark, which could have been better called 'Berlusconi'.

With this in mind, 'heads-up'

duhdek

You can fully agree with this - you don't have to be able to do everything yourself. There are enough opportunities for specialisation within the alliance. However, this means that you also have to make your specialised staff available to others, and this is where we Germans find it difficult. Whereby ... we Germans? Perhaps I should rather say the German politician ... The example of Libya shows it drastically: we could have contributed capabilities with our Tornados that are not available anywhere else in the alliance; however, the deployment would have required alliance solidarity over particular interests. There is still a need for foreign policy retraining. The Federal Ministry of Defence made a similar statement in the press around a fortnight ago - surprisingly without anyone crying foul.

You write that this cooperation was primarily initiated "from the fleet". That sounds interesting, especially because I can imagine that similar co-operations are also conceivable in the German Navy (and of course various other naval forces).

But the question that then arises in my mind is: How did the Dutch and Belgians manage to do what is probably perceived as the biggest obstacle by the other comrades in blue - how were they able to convince the politicians? In other words, why did the respective national governments see the sense of such cooperation, while others seem to find it more difficult?

Low-flying aircraft